NOLA: Compressing LoRA using Linear Combination of Random Basis

Soroush Abbasi Koohpayegani1,∗,

Navaneet K L1,∗

Parsa Nooralinejad1,

Soheil Kolouri2,

Hamed Pirsiavash1

1University of California, Davis, 2Vanderbilt University

∗ denote equal contribution

Abstract

Fine-tuning Large Language Models (LLMs) and storing them for each downstream task or domain is impractical because of the massive model size (e.g., 350GB in GPT-3). Current literature, such as LoRA, showcases the potential of low-rank modifications to the original weights of an LLM, enabling efficient adaptation and storage for task-specific models. These methods can reduce the number of parameters needed to fine-tune an LLM by several orders of magnitude. Yet, these methods face two primary limitations: (1) the parameter count is lower-bounded by the rank one decomposition, and (2) the extent of reduction is heavily influenced by both the model architecture and the chosen rank. We introduce NOLA, which overcomes the rank one lower bound present in LoRA. It achieves this by re-parameterizing the low-rank matrices in LoRA using linear combinations of randomly generated matrices (basis) and optimizing the linear mixture coefficients only. This approach allows us to decouple the number of trainable parameters from both the choice of rank and the network architecture. We present adaptation results using GPT-2, LLaMA-2, and ViT in natural language and computer vision tasks. NOLA performs as well as LoRA models with much fewer number of parameters compared to LoRA with rank one, the best compression LoRA can archive. Particularly, on LLaMA-2 70B, our method is almost 20 times more compact than the most compressed LoRA without degradation in accuracy.

Motivation

We're observing the rise of fine-tuned LLMs tailored for specific tasks. For instance, OpenAI introduced GPT Store, allowing users to fine-tune GPT models on their datasets to develop a model with specific skills or styles. Storing and managing these LLMs on hardware can pose challenges, especially as the variety of LLMs continues to grow. Our goal is to reduce the model size for each LLM variation. LoRA[1] address this limitation by finetuniung only a few additional parameters for each task. We introduce NOLA to address the limitations of LoRA. With NOLA, we can fine-tune models using fewer parameters compared to LoRA.

Let’s start with an interesting question:

We will answer to this question later. But first, let’s discuss about the limitation of LoRA.

Limitation of LoRA

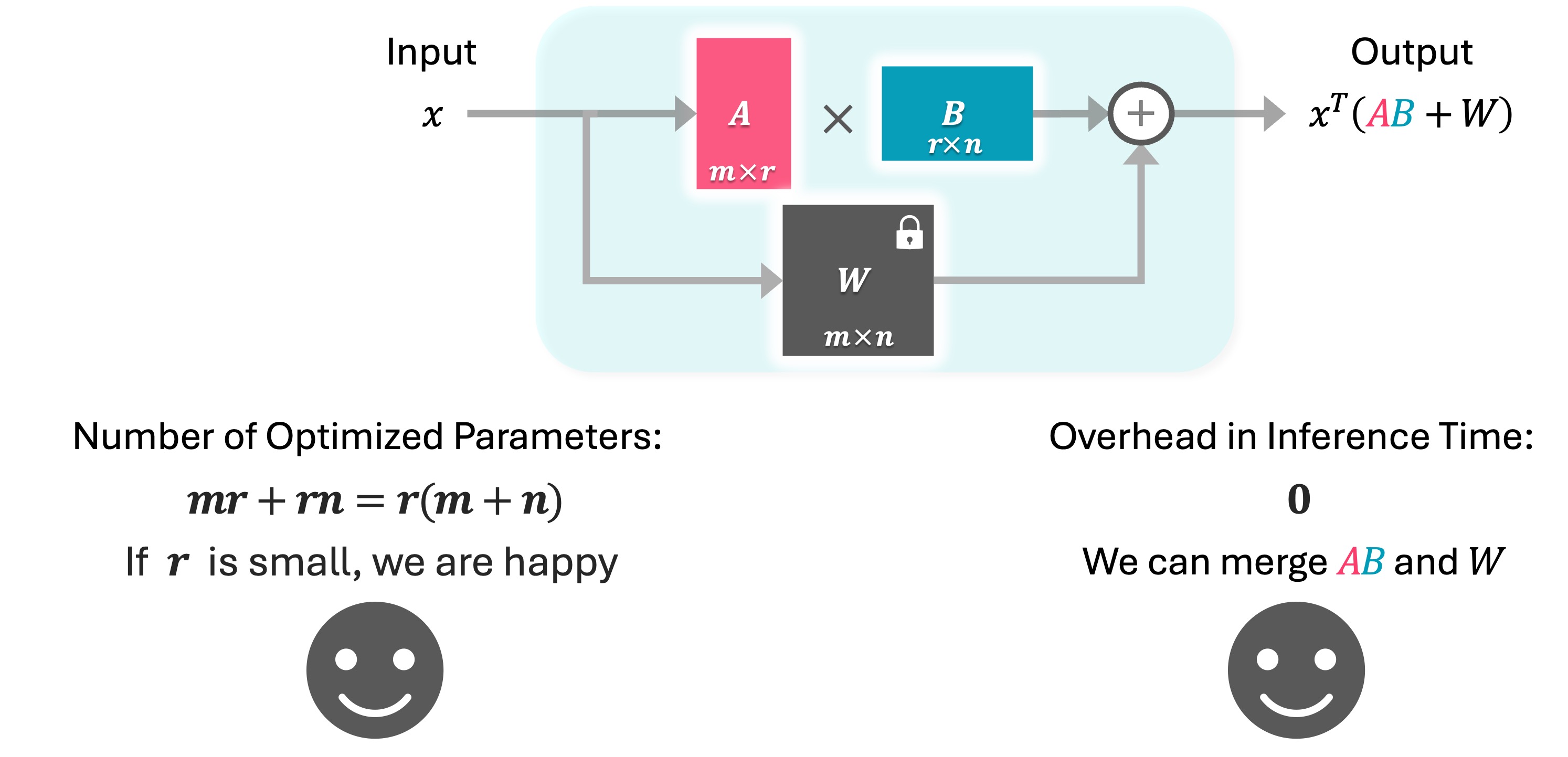

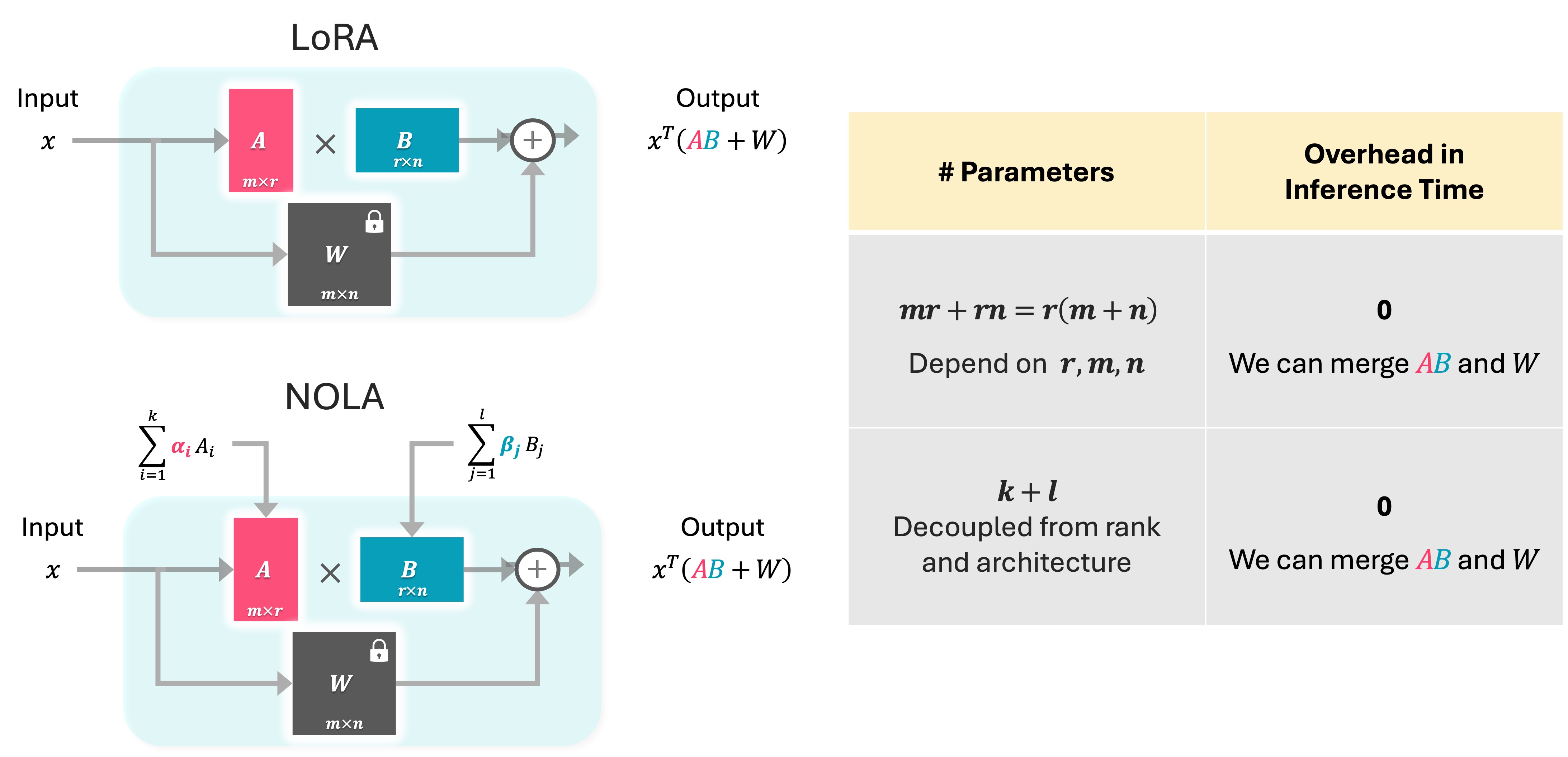

The key idea of LoRA is fine-tuning only a few parameters by constraining the changes in the weight matrix to be low-rank. Changes in the weight matrix W can be expressed as the multiplication of two low-rank matrices, A and B with rank r. So number of optimized parameters is: r x (m+n). By using a lower rank, LoRA can significantly reduce the number of optimized parameters. Note that one can merge A times B with original W, therefore LoRA does not introduce any overhead during inference time.

There are two notable limitations with LoRA. First, the number of parameters depend on the model's architecture, represented by m and n, as well as the chosen rank Second, the number of parameters is constrained by the rank one. Since rank cannot be fractional so it's impossible to decrease the number of parameters to less than m+n.

Proposed Method: NOLA

The core idea of NOLA is to reparametrizing matrices A and B in LoRA. Inspired from PRANC[2] which is published in ICCV 2023, we construct A and B as linear combinations of frozen random matrices. These random matrices serve as the basis for A and B, and during fine-tuning, we optimize only the coefficients associated with each base matrix.

we use a scalar seed and a pseudo-random generator to generate random matrices that serve as the basis for A and B. Specifically, we generate k basis for A and l basis for B. Next, we multiply each random basis by its corresponding coefficient, alphas and betas, to construct A and B. Next, we can utilize A and B for training in a manner similar to LoRA. We only optimize the coefficients and basis remain frozen during optimization.

NOLA vs LoRA

In NOLA, we only optimize k+l coefficients, So we have the flexibility to utilize any desired number of parameters during optimization. This is in contrast to LoRA, where the number of parameters is tied to the architecture and the rank. We calculate A and B using coefficients and basis, then merge them with W. This means NOLA does not have any overhead in inference time.

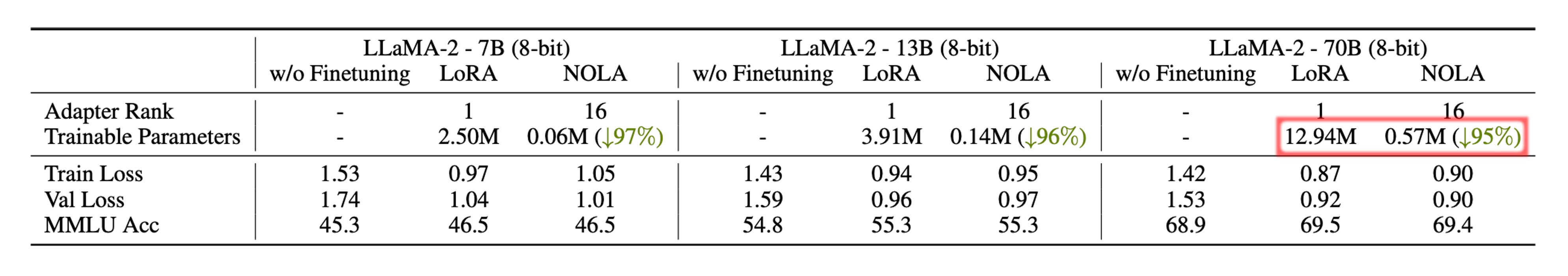

Finetuning Large Language Models

Here, we experiment with fine-tuning LLaMA 2 on the Alpaca dataset. NOLA uses 95% fewer parameters compared to LoRA with rank one, which is the smallest LoRA can do. Interestingly, since each NOLA variant needs only 0.6 million parameters, if we quantize LLaMA-70B to 4 bits, we can store and run more than 10,000 variations of LLaMA-70B on a single 48GB GPU.

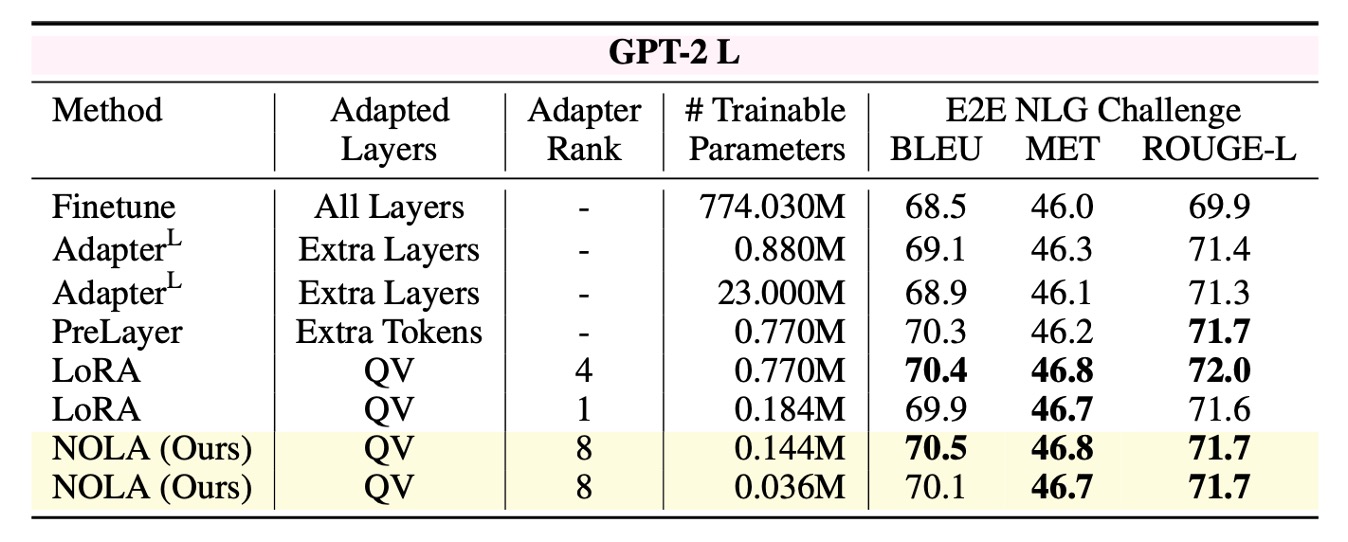

Comparision to PEFT Adapters

Compared to other baselines on GPT-2 model, NOLA achieves comparable performance while using fewer parameters. Note that we have the flexibility to adjust the number of parameters to a desired value while keeping the rank constant. This allows us to employ higher ranks and still use fewer parameters compared to LoRA with rank 1.

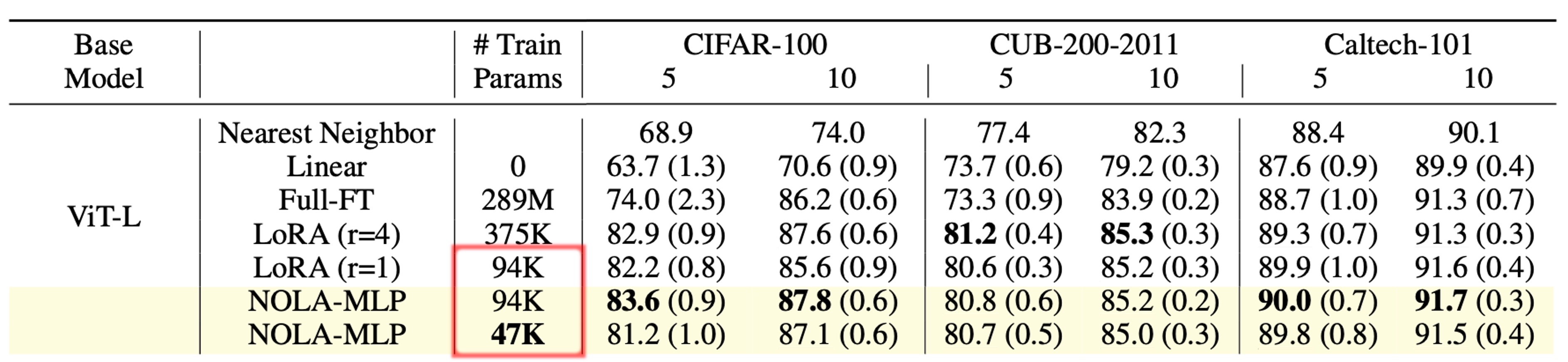

NOLA on Vision Transformers

We also evaluate NOLA on Vision transformers as well. NOLA performs on par with LoRA while using fewer parameters.

Takeaway Message: How many variations of LLaMA2-70B can we store and run on a single GPU?

With NOLA, it's feasible to store and run 10,000 variations of LLaMA-70B on a single GPU. This highlights the remarkable capability of NOLA to fine-tune large models using only a small number of parameters.

References

[1] Hu, E., Shen, Y., Wallis, P., Allen-Zhu, Z., Li, Y., Wang, S., Wang, L., & Chen, W. "LORA: Low-rank adaptation of large language models.” ICLR 2022

[2] Nooralinejad, P., Abbasi, A., Abbasi Koohpayegani, S., Pourahmadi Meibodi, K., Khan, R. M. S., Kolouri, S., & Pirsiavash, H. “PRANC: Pseudo RAndom Networks for Compacting deep models.” ICCV 2023