Constrained Mean Shift Using

Distant Yet Related Neighbors for Representation Learning

Ajinkya Tejankar1,∗,

Soroush Abbasi Koohpayegani1,∗,

K L Navaneet1,∗

, Kossar Pourahmadi1,

Akshayvarun Subramanya1,

Hamed Pirsiavash2

1University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 2University of California, Davis

∗ denote equal contribution

Abstract

We are interested in representation learning in self-supervised, supervised, or semi-supervised settings. The prior work on applying mean-shift idea for self-supervised learning, MSF, generalizes the BYOL idea by pulling a query image to not only be closer to its other augmentation, but also to the nearest neighbors (NNs) of its other augmentation. We believe the learning can benefit from choosing far away neighbors that are still semantically related to the query. Hence, we propose to generalize MSF algorithm by constraining the search space for nearest neighbors. We show that our method outperforms MSF in SSL setting when the constraint utilizes a different augmentation of an image, and outperforms PAWS in semi-supervised setting with less training resources when the constraint ensures the NNs have the same pseudo-label as the query.

Contributions

We argue that the top-k neighbors are close to the query image by construction, and thus may not provide a strong supervision signal. We are interested in choosing far away (non-top) neighbors that are still semantically related to the query image. This cannot be trivially achieved by increasing the number of NNs since the purity of retrieved neighbors decreases with increasing k , where the purity is defined as the percentage of the NNs belonging to the same semantic category as the query image.

We generalize MSF[15] method by simply limiting the NN search to a smaller subset that we believe is semantically related to query. We define this constraint to be the NNs of another query augmentation in SSL setting and images sharing the same label or pseudo-label in supervised and semi-supervised settings.

Our experiments show that the method outperforms the various baselines in all three settings with same or less amount of computation in training. It outperforms MSF[15] in SSL, cross-entropy in supervised (with clean or noisy labels), and PAWS[3] in semi-supervised settings.

We report the total training FLOPs for forward and backward passes through the CNN backbone. (Left) Self-supervised: All methods are trained on ResNet-50 backbone for 200 epochs. CMSF achieves competitive accuracy with considerably lower compute. (Right) Semi-supervised: Circle radius is proportional to the number of GPUs/TPUs used. In addition to being compute efficient, CMSF is trained with an order of magnitude lower resources, making it more practical and accessible.

Method

Similar to MSF[15], given a query image, we are interested in pulling its embedding closer to the mean of the embeddings of its nearest neighbors (NNs). However, since top NNs are close to the target itself, they may not provide a strong supervision signal. On the other hand, far away (non-top) NNs may not be semantically similar to the target image. Hence, we constrain the NN search space to include mostly far away points with high purity. The purity is defined as the percentage of the NNs being from the same semantic category as the query image. We use different constraint selection techniques to analyze our method in supervised, self- and semi-supervised settings.

We augment an image twice and pass them through online and target encoders followed by L2 normalization to get u and v. Mean-shift[15] encourages v to be close to both u and its nearest neighbors (NN). Here, we constrain the NN pool based on additional knowledge in the form of supervised labels, classifier or previous augmentation based pseudo-labels. These constraints ensure that the query is pulled towards semantically related NNs that are farther away from the target feature.

Self-Supervised Settings:

In the initial stages of learning two diverse augmentations of an image are not very close to each other in the embedding space. Thus, one way of choosing far away NNs for the target u with high purity is to limit the neighbor search space based on the NNs of a different augmentation u' of the target.

CMSF-KM: Here, we perform clustering at the end of each epoch (using the cached embeddings of that epoch) and define C to be a subset of M that shares the same cluster assignment as the target. Similar to MSF, we then use top-k NNs of target u from constrained set C for loss calculation to maintain high purity. Since augmentations are chosen randomly and independently at each epoch, cluster assignment and distance minimization happen with different augmentations. Even though members of a cluster are close to each other in the previous epoch, the set C may not be close to the current target. This improves learning by averaging distant samples with a good purity.

CMSF-2Q: We propose this method to show the importance of using a different augmentation to constrain the NN search space. In addition to M, we maintain a second memory bank M' that is exactly the same as M but containing a different (third) augmentation of the query image. We assume wi ∈ M' and ui ∈ M are two embeddings corresponding to the same image xi. Then, for image xi, we find NNs of wi in M' and use their indices to construct the search space C from M. As a result, C will maintain good purity while being diverse.

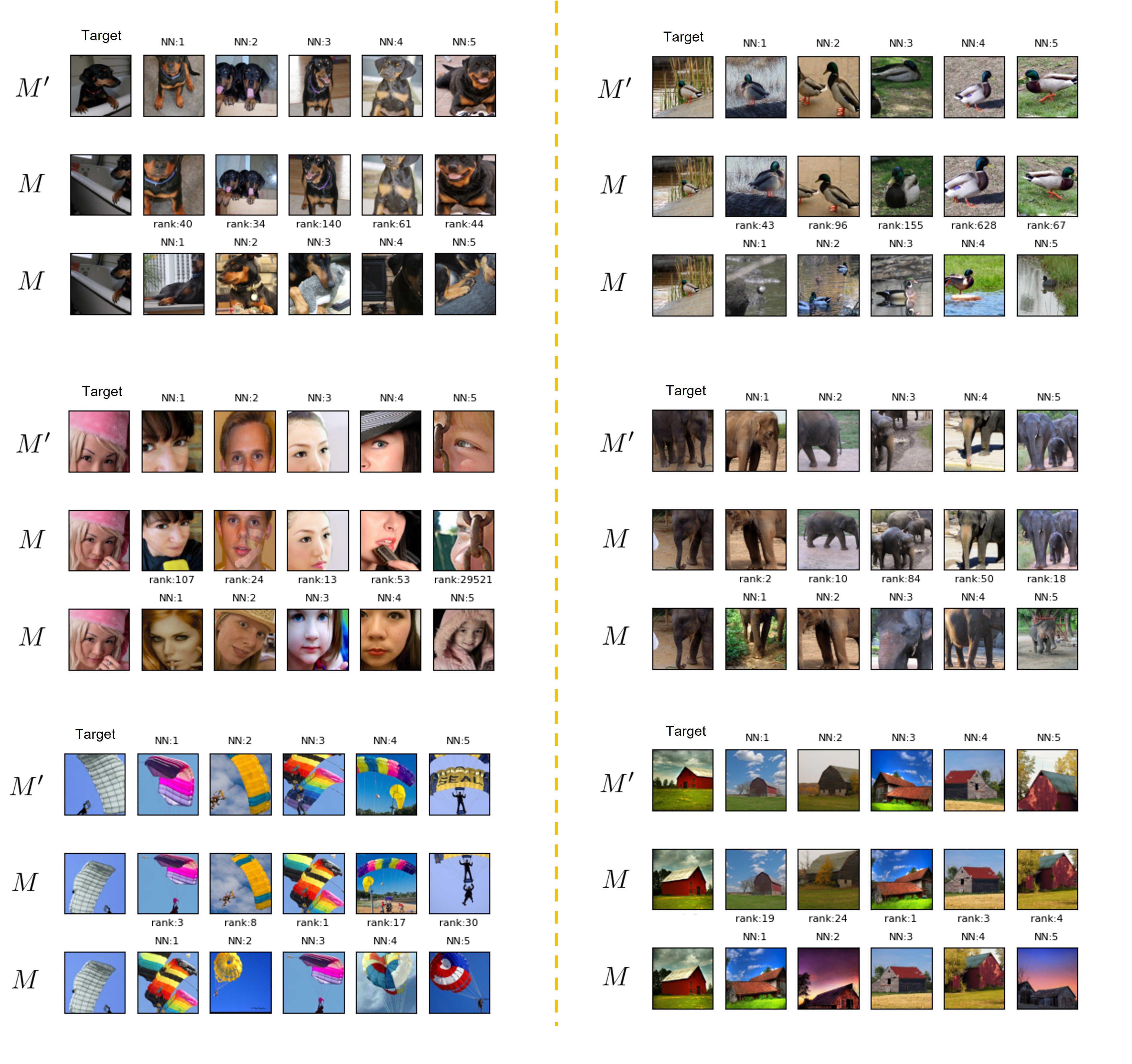

We use epoch 100 of CMSF-2Q to visualize Top-5 NN from constrained and unconstrained memory bank. First row is NNs from the second memory bank M', that is exactly the same as M but containing a different augmentation. Samples of the second row are NNs from second memory bank M' in M, therefore they are different augmentations of first row. Additionally, We show their rank in M as well. The last row is NNs from the first memory bank M. Note that constrained samples in M (second row), have high rank while they are semantically similar to the target.

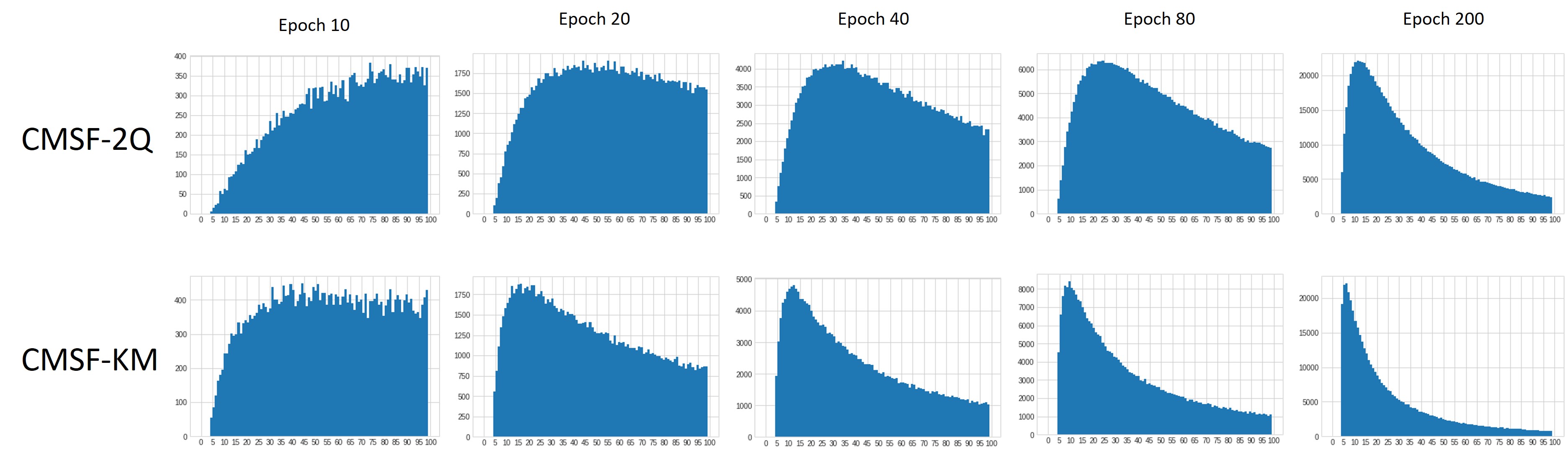

Histogram of constrained samples: We plot the histogram of constrained sample ranks in multiple stages of training of both CMSF-2Q and CMSF-KM for comparison. A large number of distant neighbors are part of constraint in the early stages of training while there is a higher overlap between constrained and unconstrained NN set towards the end of training. CMSF-2Q retrieves farther neighbors compared to CMSF-KM.

Semi-Supervised Settings:

In this setting, we assume access to a small labeled and a large unlabeled dataset. We train a simple classifier using the current embeddings of the labeled data and use the classifier to pseudo-label the unlabeled data. Then, similar to the supervised setting, we construct C to be the elements of M that share the pseudo-label with the target. Again, this method increases the diversity of C while maintaining high purity. To keep the purity high, we enforce the constraint only when the pseudo-label is very confident (the probability is above a threshold.) For the samples with non-confident pseudo-label, we relax the constraint resulting in regular MSF loss (i.e., C = M.) Moreover to reduce the computational overhead of pseudo-labeling, we cache the embeddings throughout the epoch and train a 2-layer MLP classifier using the frozen features in the middle and end of each epoch.

Supervised Settings:

While the supervised setting is not our primary novelty or motivation, we study it to provide more insights into our constrained mean-shift framework. Since we do have access to the labels of each image, we can simply construct C as the subset of M that shares the same label as the target. This guarantees 100% purity for the NNs.

Self-supervised Learning Results

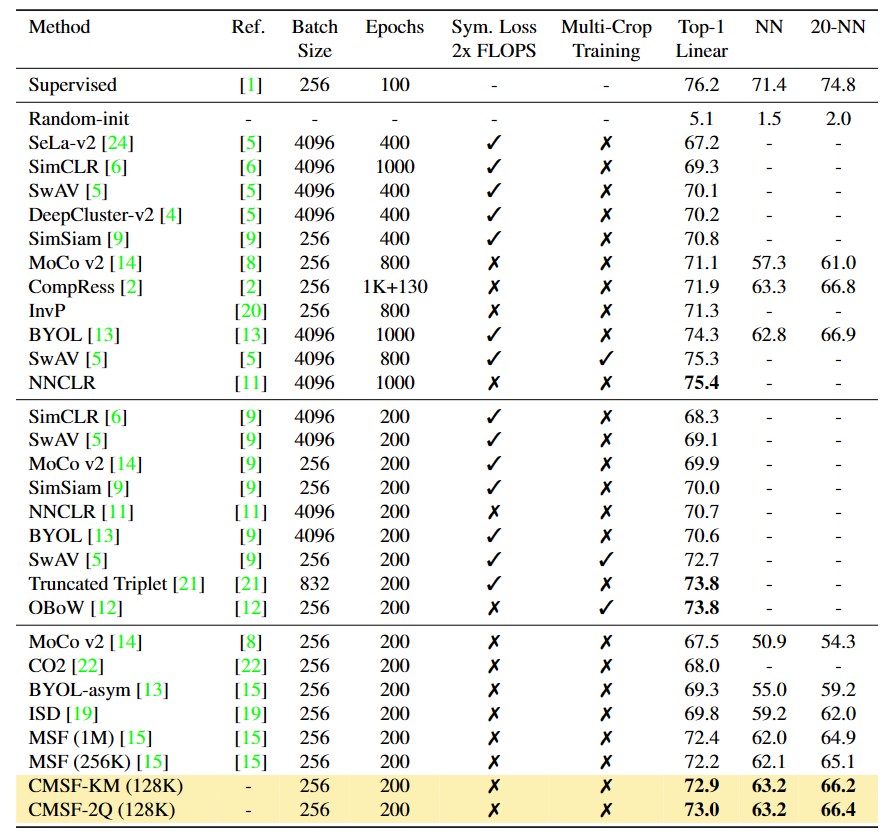

Evaluation on full ImageNet: We compare our model with other SOTA methods in Linear (Top-1 Linear) and Nearest Neighbor (NN,20-NN) evaluation. We use a 128K memory bank for CMSF and provide comparison with both 256K and 1M memory bank versions of MSF. Since CMSF-2Q uses NNs from two memory banks, it is comparable to MSF (256K) in memory and computation overhead. Our method outperforms other SOTA methods with similar compute including MSF. "Multi-Crop" refers to use of more than 2 augmentations per image during training (e.g., OBoW uses 2 × 160+5 × 96 resolution images in both forward and backward passes compared to a single 224 in CMSF). Use of multi-crops significantly increases compute while symmetric loss doubles the computation per batch. Thus methods employing these strategies are not directly comparable with CMSF.

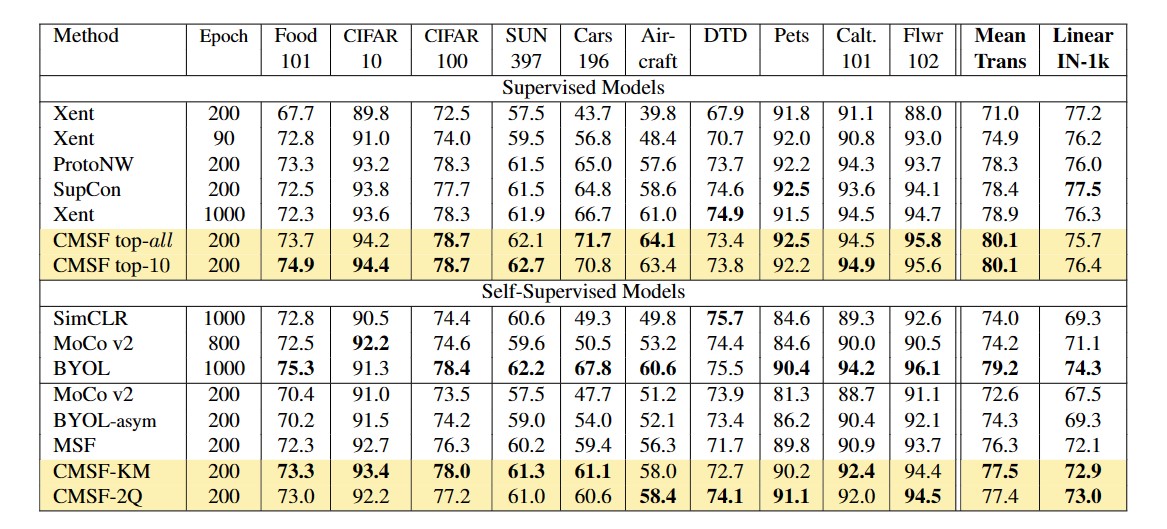

Transfer learning evaluation: Our supervised CMSF model at just 200 epochs outperforms all supervised baselines on transfer learning evaluation. Our SSL model outperforms MSF, the comparable state-of-the-art approach, by 1.2 points on average over 10 datasets.

Semi-supervised Learning Results

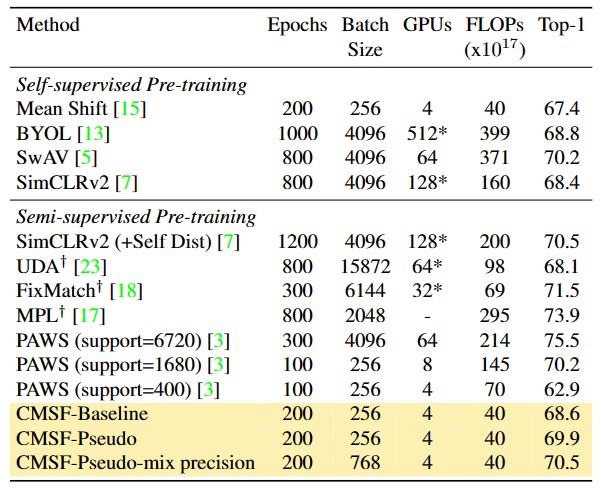

Semi-supervised learning on ImageNet dataset with 10% labels: FLOPs denotes the total number of FLOPS for forward and backward passes through ResNet-50 backbone while batch size denotes the sum of labeled and unlabeled samples in a batch. CMSF-Pseudo-mix precision is compute and resource efficient, achieving SOTA performance at comparable compute. PAWS requires large number of GPUs to be compute efficient and its performance drastically drops with 4/8 GPUs. † Trained with stronger augmentations like RandAugment[10]. ✱ TPUs are used.

References

[1] Torchvision models.https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/torchvision/models.html.

[2] Soroush Abbasi Koohpayegani, Ajinkya Tejankar, and Hamed Pirsiavash. Compress: Self-supervised learning by compressing representations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 2020.

[3] Mahmoud Assran, Mathilde Caron, Ishan Misra, Piotr Bojanowski, Armand Joulin, Nicolas Ballas, and Michael Rabbat. Semi-supervised learning of visual features by non-parametrically predicting view assignments with support samples. ICCV, 2021.

[4] Mathilde Caron, Piotr Bojanowski, Armand Joulin, and Matthijs Douze. Deep clustering for unsupervised learning of visual features. InProceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), pages 132–149, 2018.

[5] Mathilde Caron, Ishan Misra, Julien Mairal, Priya Goyal, Piotr Bojanowski, and Armand Joulin. Unsupervised learning of visual features by contrasting cluster assignments. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 9912–9924. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020.

[6] Ting Chen, Simon Kornblith, Mohammad Norouzi, and Geoffrey Hinton. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.05709, 2020.

[7] Ting Chen, Simon Kornblith, Kevin Swersky, Mohammad Norouzi, and Geoffrey E Hinton. Big self-supervised models are strong semi-supervised learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33:22243–22255, 2020.

[8] Xinlei Chen, Haoqi Fan, Ross Girshick, and Kaiming He. Improved baselines with momentum contrastive learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.04297, 2020.

[9] Xinlei Chen and Kaiming He. Exploring simple siamese representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.10566,2020.

[10] Ekin Dogus Cubuk, Barret Zoph, Jon Shlens, and Quoc Le. Randaugment: Practical automated data augmentation with a reduced search space. In H. Larochelle, M. Ranzato, R. Hadsell, M. F. Balcan, and H. Lin, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 33, pages 18613–18624. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020.

[11] Debidatta Dwibedi, Yusuf Aytar, Jonathan Tompson, Pierre Sermanet, and Andrew Zisserman. With a little help from my friends: Nearest-neighbor contrastive learning of visual representations, 2021.

[12] Spyros Gidaris, Andrei Bursuc, Gilles Puy, Nikos Komodakis, Matthieu Cord, and Patrick Perez. Obow: Online bag-of-visual-words generation for self-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pages 6830–6840, June 2021.

[13] Jean-Bastien Grill, Florian Strub, Florent Altche, Corentin Tallec, Pierre H Richemond, Elena Buchatskaya, Carl Doersch, Bernardo Avila Pires, Zhaohan Daniel Guo, Mohammad Gheshlaghi Azar, et al. Bootstrap your own latent: A new approach to self-supervised learning. arXiv preprintarXiv:2006.07733, 2020.

[14] Kaiming He, Haoqi Fan, Yuxin Wu, Saining Xie, and Ross Girshick. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. InProceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 9729–9738, 2020.

[15] Soroush Abbasi Koohpayegani, Ajinkya Tejankar, and Hamed Pirsiavash. Mean shift for self-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pages 10326–10335, October 2021.

[16] Ishan Misra and Laurens van der Maaten. Self-supervised learning of pretext-invariant representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.01991, 2019.

[17] Hieu Pham, Zihang Dai, Qizhe Xie, and Quoc V Le. Meta pseudo labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 11557–11568, 2021.

[18] Kihyuk Sohn, David Berthelot, Nicholas Carlini, Zizhao Zhang, Han Zhang, Colin A Raffel, Ekin Dogus Cubuk, Alexey Kurakin, and Chun-Liang Li. Fixmatch: Simplifying semi-supervised learning with consistency and confidence. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 2020.

[19] Ajinkya Tejankar, Soroush Abbasi Koohpayegani, Vipin Pillai, Paolo Favaro, and Hamed Pirsiavash. ISD: Self-supervised learning by iterative similarity distillation, 2020.

[20] Feng Wang, Huaping Liu, Di Guo, and Sun Fuchun. Unsupervised representation learning by invariance propagation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 33, pages 3510–3520. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020.

[21] Guangrun Wang, Keze Wang, Guangcong Wang, Philip H. S. Torr, and Liang Lin. Solving inefficiency of self-supervised representation learning, 2021.

[22] Chen Wei, Huiyu Wang, Wei Shen, and Alan Yuille. Co2: Consistent contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02217, 2020.

[23] Qizhe Xie, Zihang Dai, Eduard Hovy, Minh-Thang Luong, and Quoc V Le. Unsupervised data augmentation for consistency training. NeurIPS, 2020.

[24] Asano YM., Rupprecht C., and Vedaldi A. Self-labelling via simultaneous clustering and representation learning. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.